18.12.2020 - 10:09

|

Actualització: 18.12.2020 - 11:09

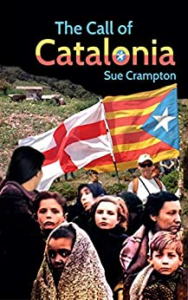

Sue Crampton’s “The Call of Catalonia”, apart from being a good read, is a book that will be useful to those wondering what the recent kerfuffle was about with the Catalans and their 2017 Referendum. Who are those Catalans anyway, aren’t they just mean Spaniards? Or bolshy French? OK, this book is no history book nor political treatise and doesn’t intend to be. But it does give clues about a partially invisible country set between Spain and France which still suffers the kind of tribulations that most Europeans put behind them 75 years ago. In Sue Crampton’s own words “as you read these stories, I hope that you will begin to understand something about the Catalans’ love for their country and their struggle”.

In the first two lines of the first story, “A magical trail”, the almost initiatory intention of her book is revealed: “Wave a wand. France and Spain disappear and before your eyes the magical frontier land of northern Catalonia emerges”. Indeed, the reader wanders through a kaleidoscope of short stories that conjure up places and moments of Catalan life and history the writer introduces you to: the description of a much beaten trail leading into exile, the struggle of the Ibers against imperial Rome, the first Catalan woman to lead a trades union, the first women’s strike in France led by Catalan women, an imaginary meeting with a convalescent George Orwell, the Catalan “Diada” or national day…

All these mini stories, and the longer ones at the end, help the reader to see not only the worrying parallelisms between Catalonia under Franco and Catalonia today, but also the mystery of a country that for years (2012-2017) could regularly unite a million marchers – including Sue and her husband Ross – in the streets to demand self-determination. It may also help to understand why they have instinctively recoiled into their tortoise shell in self-defence mode as Madrid’s fierce repression (3000 now persecuted) gets under way Erdogan-style. The Catalans indeed have a word for this: seny, a quality the Scots doubtless share, but do not have such dire need for. Certainly dealing with Westminster is not the same as dealing with neo-Francoist Spain. One thing is a country in the hands of Thatcherite brexiteers, another to be in the hands of bogus judges who make little attempt to veil their far-right sympathies and phobia for things Catalan. As Sue Crampton says in a memorable final poem, comparing the horrors of Argelers beach concentration camp in 1939 and the mass attacks on Catalan voters on October 1 2017:

Franco’s legacy

An ugly relic of a war where

Democracy was strangled.

And now the horror begins again…

“The call of Catalonia” tells us things about Catalonia that only someone who has lived there can convey. It speaks of a country that no Lloret de Mar balcony-jumper nor EU comissioner is likely to ever get a sniff of. Written with sympathy and feeling, it offers an insight into a nation that lends itself to various levels of interpretation in an age in which identity – anybody else’s, that is – seems to have become a dirty word in this “pull-up-the-ladder-Jack” world. Sue Crampton’s relationship with Catalonia, particularly with the privileged Girona region, is comparable in some ways to the emotional ties so many “cultivated” Britons – excuse the term – have historically had with Provence or Tuscany. Those who would never have had tea with Mussolini that is. She and her husband form part of that special race of Britons who have penetrated the often opaque reality of Girona and fallen in love with what they saw.

This of course brings her close to other famous Costa Brava residents. We could mention John and Patricia Langdon-Davies – Sardana dance enthusiasts and heroic protectors of the orphans of the Civil War. Or, in quite another sense, the very British Hooper sisters, one of whom chose such an un-British cemetery as Cadaqués’ as her last abode. It also includes academics such as Henry Ettinghausen – a brave denouncer of today’s neo-Francoism and proud member of the Dignity Commission – or writer Tom Sharpe, who fell in love with the Catalan public health system and wisely died before Covid19 revealed it to be the papier maché façade that the cuts in the sector turned it into. On the business side, mention must be made of Nancy Johnstone, who set up a hotel in Tossa back in 1934, before tourism even existed, or Adrian Buckley, the creator of Diana Darts – a hugely successful dartboard distributor – whose English wife Diana teaches Catalan to young Moroccans as volunteer work to boot. They are all personalities that have seen something special in a land whose beauty is evident to all, but whose spirit often needs some searching for. And that is where Sue Crampton comes in.

As an exiled ex speaker of the Catalan government, Antoni Rovira i Virgili once said that a landscape is but a landscape if we can’t perceive its spirit, the essence and story that lie within it. Living nine years in Girona enabled Sue Crampton to do just that. She delves into people, episodes and landscapes to unearth the untold epic – large or small – they conceal. A task to which she has applied the full prowess of her imagination. She comes up with events many locals might not even have heard of, a factor that does not make them any less relevant nor revealing. (The book must surely be translated into Catalan!) Particularly appealing are the stories that deal with the frontier and famous Port Bou station, where so many lives were saved by crossing the Pyrenees, that great ideological-cum-stone barrier that has for so long helped intolerant Spain to fence Catalonia off from the free-thinking world. May I confess that I came out in goose bumps when I read her stories about France’s first women’s strike – headed by Catalan women – or about Catalonia’s first acknowledged woman trade union leader – Isabel Vila (about whom a play is currently being staged) –or about the Civil War experiences of my own in-laws. They are the sort of stories and legends that Francoism did its utmost to stamp out in a country where dictatorships have for so long laid down what is to be remembered and what forgotten. Or worse still, condemned. It is the sort of book that I had always hoped someone would write.

[This book review was originally published by Brave New Europe].