09.11.2018 - 10:00

|

Actualització: 09.11.2018 - 11:00

Of the many lessons we learnt from Montesquieu, one of the most important ones is that “no tyranny is more cruel than that which is practiced in the shadow of the law and with the trappings of justice”. The quote is taken from the author’s Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, a book where the distinguished Gascon describes how Tiberius always managed to find some judge in Rome who was willing to unjustly convict anyone that got in his way politically.

Nowadays Montesquieu and Rome might seem to be too ancient a reference, but they are not. The essay on the rise and fall of the empire must be one of the most influential works in the political history of humankind. So much so that, when they first considered setting up a special court in Nuremberg to try Nazi crimes, Montesquieu’s words warning of a judicial tyranny were instrumental in the decision to ensure that not only politicians sat in the dock, but also judges, court officials and prosecutors. Specifically, sixteen Nazi jurists, judges and attorneys were tried and found guilty of war crimes during the third trial. This was a momentous feat, probably the most dramatic moment of the 20th century, when the world had to come up with no less than a suitable jurisdiction to adequately punish the worst crime every witnessed by humankind.

During the Nuremberg trials, one of the most interesting debates was to what extent it was Germany as a nation or the Third Reich that was being put on trial, and to what extent, therefore, single individuals might be convicted. Justice Jackson’s well-known statement resolved the dilemma. Jackson warned that crimes should not be regarded merely as the work of an abstract, metaphysical entity —a nation— because it took real people —toiling and sweating— to carry them out. The link between the individual actions for which someone was being prosecuted and the general picture of the aggression, indeed the collective brainchild of the Reich, provided Jackson with the key to ensure that those individual judges —who always claimed to be acting within the law at the time and following orders from their superiors— would not get away with and would pay for their crimes, rather than use the law to take cover.

This week the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Arnaldo Otegi, Rafa Díez, Sonia Jacinto, Miren Zabaleta and Arkaitz Rodríguez had been denied a fair trial and that Spain’s Audiencia Nacional [a special court that sees major crimes] had violated the European Convention on Human Rights. Specifically, the European court ruled that judge Angela Murillo was blatantly biased, first in the Gatza case and then during the Bateragune trial. The European court states that Murillo’s bias is “clearly incompatible” with her office as judge and admits that the defendants were right —but promptly ignored— when they queried the impartiality of the other two judges, Juan Francisco Martel and Teresa Palacios, who eventually sentenced them to six and a half years in prison.

Nevertheless, the Strasbourg ruling comes very late. Following an unjust trial which —like Tiberius did in Ancient Rome— merely sought to push out of public life people who bothered the Spanish government at the time, Arnaldo Otegi and his associates were convicted and spent between six and six and a half years in prison. In this case, as Otegi himself has pointed out, the one particularly grave fact is that we all know Catalonia’s pro-independence leaders are headed in the same direction [as their Basque counterparts]: they will be found guilty after an unjust trial and only years later will Europe make amends, once the court’s decisions have made their impact on political life and the lives of innocent people have been severely damaged. That is the way Strasbourg works. To witness and to be aware of that, precisely where we stand today, is outrageous and most unfortunate, indeed.

However, it should be pointed out that Spain’s collection of unfavourable rulings keeps growing, which proves beyond all doubt that Madrid’s exceptional courts of law are actually indecent political tools that are instrumental in the perpetuation of injustice. There is plenty of evidence that this is neither an anecdote in a trial nor a one-off technical error, but that there is a system in place which serves the powers that be. On this point, I wonder if the time has come to start arguing internationally that the abnormal behaviour of Spain’s top judiciary, which repeats itself with every political trial, demands a Nuremberg, a trial where they are held to account. Not just the system itself, but the individual people. One day the likes of Murillo and Llarena ought to pay for their crimes, if necessary before an international court of law or perhaps before a Catalan court, once Catalonia is independent. As shown in Nuremberg in 1945 by the honourable Robert H. Jackson, this tyranny that has befallen (and will befall) several concrete human beings, all of whom have a name and surname, would simple not have existed without these individuals’ personal efforts and dedication. It would have never happened.

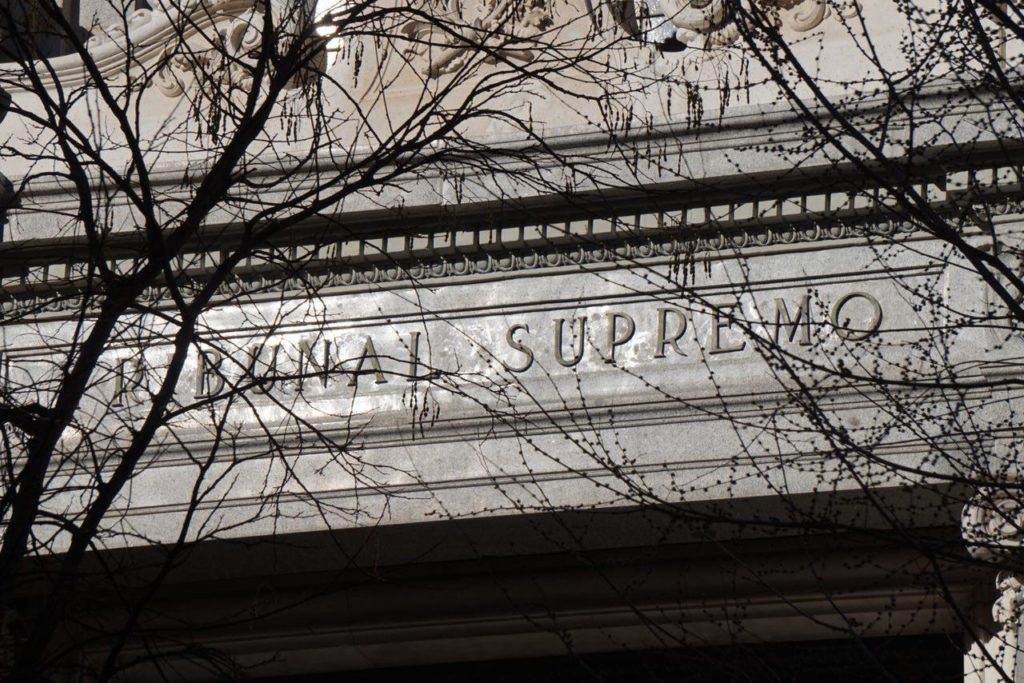

PS: Also this week Spain’s Supreme Court has shown how pliable it is when it comes to appeasing banks: it has had no qualms about reversing its original decision to make banks (rather than borrowers) pay mortgage tax, thus saving them a pretty penny. Truly shocking …