15.07.2019 - 07:19

|

Actualització: 15.07.2019 - 09:19

Opponents of Catalan independence often describe the movement as ‘populist’. The intent of this characterization is to highlight similarities between the Catalan indpendence movement and populist movements with generally negative reputations, such as Brexit, Marine Le Pen’s National French, Donald Trump’s Republican party, the right-wing Spanish party Vox, Latin American Chavismo, etc.

‘Populist’ is hard to define, and multiple definitions exist. It is, to some researchers, an ideology (Arter 2010). To others, it is an oratory ‘style’ (Moffitt and Tormey 2013). The definition is so loose that one expert on the topic says ‘any political actor who is in the news frequently for a substantial amount of time probably runs the risk of being labeled ‘populist’ sooner or later’ (Bale, Kessel, and Taggart 2011).

Since it is nearly impossible to define what populism is, it’s nearly impossible to say whether a movement, party, or person is itself ‘populist’. Too many definitions exist, allowing anyone to make the case that their political opponents are ‘populists’.

So, let’s take another approach. Rather than focusing on (the impossible question of) what populism is, let’s instead focus on who populists are. Reliable data exist in multiple countries on the demographic, social, and political characteristics of those who support movements that are generally recognized as being populist in nature (UK Brexit, Trump, etc.). An overview of the academic literature regarding the who of modern populism reveals five general characteristics:

- Low education: Populism receives most support from those with low education (Waller et al. 2017).

- Low income: Populism receives most support from those with low incomes (Pikkety 2018).

- Xenophobia: Populism receives most support from those who are opposed to immigration and outsiders (Rydgren 2003).

- Unhappiness: Populism receives most support from those who are discontent, not only with politics, but with life/society in general (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck 2016).

- Authoritarianism: Populist movements often aspire for more ‘mano dura’ practices (penal populism), stemming from authoritarian attitudes about obedience and the law, etc. (Pratt and Miao 2018)

The question

Is the Catalan independence movement ‘populist’?

The methods

We’ll examine survey data from Catalonia related to the above 5 characteristics in an effort to understand the extent to which it is factually accurate to classify independentism as ‘populist’ or not, based on the extent to which the views of pro- and anti-independence Catalans match the 5 characteristics described above.

The results

Finding 1: Education

Low levels of education are associated with support for populist policies and politicians in both developing and developed countries. Chavismo in Venezuela, for example, was a movement largely driven by the uneducated. Support for Donald Trump in the 2016 US presidential elections was highest in areas with low education (even after adjusting for income). And votes in favor of Brexit largely came from those without high levels of education (below):

If the Catalan independence movement were ‘populist’ in nature, we would expect that those in favor of independence – like their populist counterparts elsewhere – would have low levels of education. But when we actually examine the data, the opposite trend appears. The below chart shows the association between support for independence and level of education. The association is strong and clear: the more one is education, the more in favor he/she is of indepenence:

Finding 2: Income

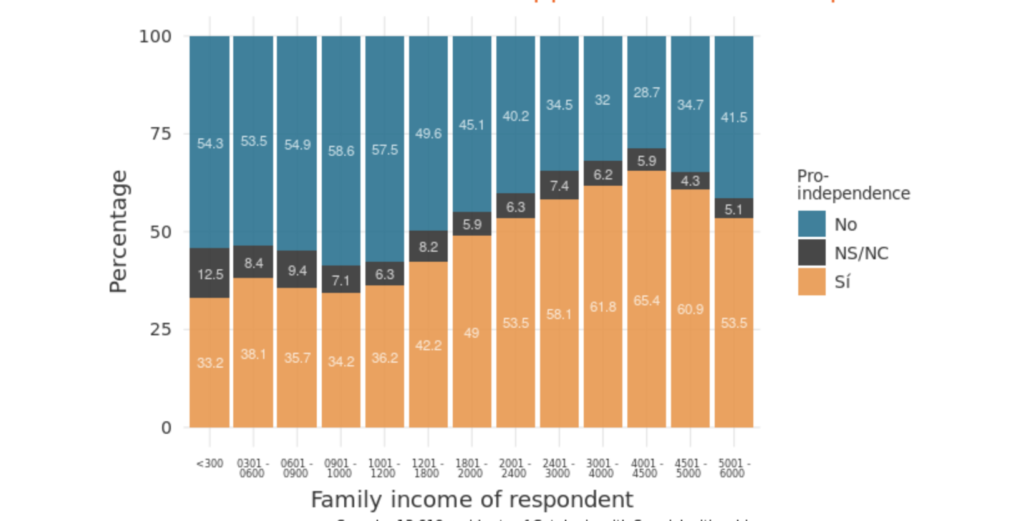

Income and education are closely correlated. It is should come as no surprise then that since the bulk of support for union with Spain in Catalonia comes from those with low levels of education, it also comes from those with low income. In other words, there is truth to the accusation that the Catalan independence movement is a movement of the elites or rich: it is! But a movement cannot be simultaneously ‘populist’ and ‘elitist’, since a general characteristic of populist movements is counterposing the people and the elites.

The below chart shows the association between income and support for indepenence in Catalonia. If the indepenence movement were ‘populist’ in nature, we would expect support to greatest among those with low levels of education. Instead, we see the opposite pattern: in the lowest income groups (0 to 1200 euros per month), support for union with Spain is majority. But among the wealth (2000 or more euros per month), support for independence is high.

Finding 3: Xenophobia

One issue associated with populism is xenophobia. Populist movements often use binary rhetoric which juxtaposes ‘us’ and ‘them’. Because of the ‘separatist’ nature of the Catalan independence movement, the accusation that the movement is xenophobic and populist in nature is frequent.

But the data, again, show the opposite. When asked whether they agree or disagree with the xenophobic phrase ‘with so much immigration, one no longer feels at home’, a majority of pro-indepenence Catalans (60.3%) disagree, and only one quarter (25.6%) agree. But among Catalans in favor of union with Spain, only a minority reject the xenophobic phrase (47.2%) and 4 in 10 (40.5%) agree with it. In other words, to the extent that we accept that xenophobia is an integral part of populism, we must also accept that Catalan unionism is more ‘populist’ than Catalan independentism.

Finding 4: Unhappiness

Populism thrive on general discontent. According to Spruyt et al, ‘populism is embedded in deep feelings of discontent, not only with politics but also with societal life in general’ (Spruyt, Keppens, and Van Droogenbroeck 2016). Accordingly, if Catalan independentism were populist, we would expect that pro-independence Catalans would be less happy than their anti-indepenence counterparts. Is this the case?

No. Catalans of all political stripes are generally happy witht their personal lives (average of approximately 7 of 10 on a 0-10 scale). But pro-independence Catalans are actually slightly happier than their pro-union counterparts. Again, this does not fit the pattern of populist movements elsewhere.

Finding 5: Authoritarianism

Movements generally considered to be populist often exhibit a ‘hard-line’ stance on crime, and seek high levels of obedience from their followers. The authoritarian nature of these movements is no secret: one of the keys to Trump’s electoral success was his ‘law and order’ attitude, and analysis of the attitudes of Brexit voters in the UK also show an authoritarian tilt:

Do we find this same attachment to authoritarianism among Catalan independentists? Gauging authoritarian attitudes is not straightforward, but data do exist on the subject. For example, when asked about the extent to which schools should teach children to obey authority, Catalan unionists exhibit much higher degrees of authoritarian attitudes than their independentists counterparts:

By the same token, the rate of Catalans who say that ‘the law should always be obeyed in any circumstances’ is nearly twice as high among anti-independence Catalans than their pro-independence counterparts.

In other words, if the Catalan independence movement were ‘populist’, we would expect that it would share with other populist movements an affection for obedience, law, and order. But the data show, once again, the opposite.

Conclusion

The term ‘populist’ is problematic, since no commonly accepted definition exists. By focusing on who populists are, rather than what they are, we can get around the problem of not having a clear definition, and instead dive right into the more relevant question: whether people who support Catalan independence are like supporters of populist movements elsewhere.

In this regard, the Catalan independence movement is not populist. Relative to Catalans in favor of continued union with Spain, pro-independence Catalans are (i) more educated, (ii) wealthier, (iii) less xenophobic, (iv) more satisfied with their personal lives, and (v) less authoritarian. In fact, by these measures, the pro-union movement appears to embody populist tendencies much more than the pro-independence movement. Catalans in favor of union with Spain exhibit all five of the characteristics of populist movements elsewhere: they are (i) less educated, (ii) less wealth, (iii) more xenophobic, (iv) less satisfied with their personal lives and (v) more authoritarian.

One could argue that the cultural ‘identity’ issue of Catalan independentism makes the movement inherently populist. That is, since Catalan-speakers and those who self-identify as more Catalan than Spanish are generally pro-independence, this makes independentism ‘populist’. This is a common refrain in Spanish politics: that Catalan independentists are populist since their politics are driven by identity. But if one accepts such a thesis, then unionism must also be considered equally ‘populist’ since its support also relies on clumping by language and culture: those who speak Spanish mainly and who self-identify as Spanish largely vote for unionist policies.

Ultimately, the ‘populist’ label is so devoid of meaning, so controversial in content, and so flexible as to be applied to almost any political movement. Perhaps, then, the term simply should not be used. I personally avoid it entirely (with the notable exception of this article) because of its lack of agreed-upon meaning.

But if we (society) are going to use the term ‘populism’, then we should use so with at least some degree of rigor, and in line with the reality of objective data. And the data are clear on this matter: the Catalan independence movement is many things – but it is not populist.