31.10.2019 - 10:43

|

Actualització: 31.10.2019 - 11:43

The Spanish Government has been making a concerted effort to depict Catalonia as a divided society. The notion of a “divided” or “fragmented” Catalonia fits well with Spanish President Pedro Sánchez’s refusal to dialogue with Catalan representatives about the current political crisis. The argument goes like this: before Spain can consider dialogue with Catalonia, “Catalonia must enter into a dialogue with itself”. In other words, because Catalans are in disagreement, there is no sense in Spain taking any action.

It’s a questionable strategy, even if we assume its underlying premises to be true. But there’s another problem with Spain’s inaction and refusal to dialogue: the underlying premise of a divided Catalonia is false. Yes, Catalans are split on the question of independence (hence the call for a referendum, to clarify the numbers). But No, Catalonia is not a “divided society”, at least in terms of the causes and solutions for the current political crisis. On the matters of (1) the imprisonment of Catalan politicians and social activists, and (2) the right to self-determination, Catalonia is actually fairly united. Let’s dig into the data.

1. A broad consensus against the imprisonment of Catalan representatives

The cause of the unrest in Catalonia over last week is not just Catalonia’s independence. On this matter, few minds have changed over the last few years.

The cause of the recent unrest was the sentencing of a dozen Catalan politicians and activists to between 9 and 13 years of prison each for having organized an independence referendum. They were convicted of “sedition” (a crime of violence), despite never having never used, accepted, or encouraged any acts of violence. At the time of conviction they had already spent up to two-years in “preventive” prison, and – despite several of them being elected and re-elected to office – have been prohibited from carrying out their political duties.

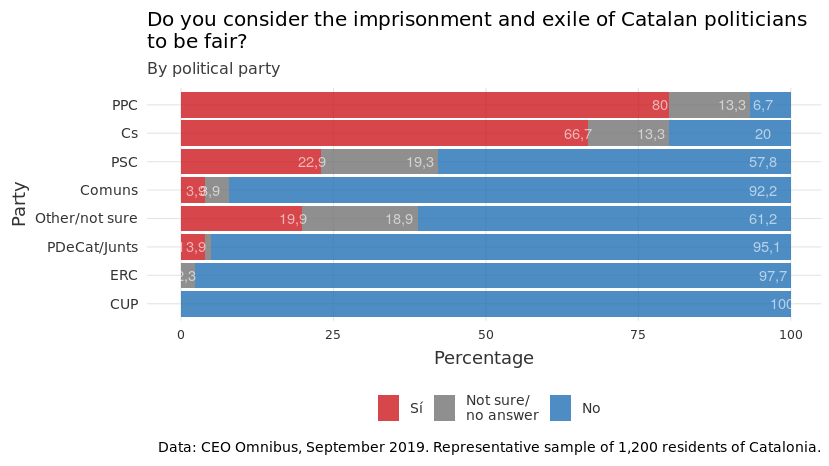

On the matter of these imprisonments, there is a clear consensus in Catalonia. Only 18% of Catalans consider the imprisonment of their politicians to be fair, 14% aren’t sure and more than two-thirds of Catalans considers say that imprisonment is not fair.

Only in two hard-line Spanish nationalist parties (the Popular Party – PPC, and Citizens – Cs) is there support for imprisoning the Catalan politicians. In the pro-independence parties, expectedly, there is virtual unanimity against imprisonment. But what’s most striking is the stance of the anti-independence, left-leaning parties. 92% of the voters of the leftist “Comuns” party consider that the imprisonment of Catalan politicians is unjust, and 58% of Catalan socialists consider it unjust.

2. A broad consensus in favor of self-determination

In Catalonia, there is a broad consensus in favor of self-determination. This consensus naturally includes all those who are in favor of independence, but also significant portions of Catalans who are opposed to independence. In other words, most Catalans – including many who wish to remain part of Spain – want to decide the issue through a referendum.

The most recent survey on the subject asked 1.200 systematically sampled Catalans the extent to which they agree with the following phrase: “A referendum should take place in Catalonia so that Catalans can decide what relationship they want there to be between Catalonia and Spain” (“S’hauria de fer un referèndum a Catalunya perquè els catalans i les catalanes decidissin quina relació volen que hi hagi entre Catalunya i Espanya”). The results are below.

Only 21.2% of Catalans are opposed to a referendum. More than two-thirds are in favor (and if we remove the 11% who don’t have an opinion on the matter, the percentage in favor is 76%).

It’s important to emphasize that this is not a one-off, spurious result. This has been the case for at least those years for which reliable data are available, and the pro-referendum majority (about 75%) remains constant even when you formulate the question differently. For details on this, see my article here.

It’s also worth noting that significant portions of voters of anti-independence parties are actually pro-referendum. For example, fewer than 10% of Comuns voters oppose a referendum, and the Catalan socialists are split 50-50 on the matter.

In Catalonia, enthusiasm for a referendum is greatest on the left, but garners support from the center and center-right as well. The only political sector where opposition to a referendum is greater than support for it is among Catalans who self-classify as “far right”.

Among Catalans born in Catalonia (most are), nearly 80% want a referendum, and only 15% oppose. Catalans born in the rest of Spain, or abroad, also favor a referendum, albeit by a lesser margin.

Conclusion

Pedro Sánchez’s government is right to say that Catalonia is divided regarding independence: about half want it and about half don’t (the numbers vary from survey to survey, but are fairly close to a 50-50 split over the last two years). This is the norm in democracy: people disagree on things, but agree on settling their disagreements democratically. In other words, differential preferences for a political outcome does not necessarily mean disagreement on how the outcome should be decided. In fact, if there weren’t disagreement on independence, there would be no need for a vote (since the result would already be known), as is the case in almost every region in every country of the world.

Catalans are overwhelmingly opposed to the imprisonment and exile of their elected politicians, and they are overwhelmingly in favor of a self-determination referendum. These two consensuses explain the popular revolt taking place in Catalonia, as well as the political deadlock. Two address the Catalonia-Spain conflict, President Sánchez would be wise to recognize that on these questions, Catalans are largely in agreement. In other words, the disagreement is not between Catalans, but rather between (a) the consensus solution proposed by Torra’s Catalonia (freedom for the imprisoned politicians and a self-determination referendum) and (b) the counter-offer being made by Sánchez’s Spain (law and order).