11.08.2019 - 11:12

|

Actualització: 11.08.2019 - 13:12

The similarities between Scotland and Catalonia are obvious:

- Both Catalonia and Scotland are currently part of States generally recognized as functioning democratic societies (Spain and the U.K.)

- Similar size (Catalonia = 7,6 million, Scotland = 5,4 million)

- Both have a strong sense of “national” identity

- Approximately half of Scots and half of Catalans want an independent State

- Both Scots and Catalans are largely pro-EU

- Both Scots and Catalans have their own language (though Catalan is far more widely spoken than Gaelic)

When Scots decided to vote on the question of independence in 2014, it was a relatively undramatic event. No judges ordered ballot boxes to be siezed. No police were sent from the rest of the U.K. to beat voters. No Scottish activists were placed in prison. A trial for “rebellion” was not held in London. A referendum simply took place, the votes for “No” outnumbered those for “Yes”, and life went on.

With Brexit on the horizon, a majority of Scots want to vote on the question of independence again. And they likely will. And, like the 2014 vote, nobody will be beaten, nobody will be arrested, nobody will be brought to the State’s capital for a political trial, and the question of the U.K.’s “governability” will likely be unaffected by both the process and the outcome of the next Scottish self-determination referendum.

The same cannot be said for Catalonia and Spain. The leaders of the main pro-independence Catalan parties have spent more than a year and half in “preventive” prison for organizing the 2017 Catalan referendum, and Spain’s political stability is increasingly doubtful (acting President Pedro Sánchez was unable to obtain a majority in congress last month, and Spaniards may go to the national polls for the fourth time in five years this fall). The outcome of the Catalan referendum – and Spain’s reaction to it – has been largely negative for all parties. Why, then, has Spain not simply taken the approach of the U.K?

The simple, ubiquitous answer from the Spanish government is because “it’s illegal”, a response which begs the obvious follow-up question: if the law is the problem, why not change it? Why not make it explicitly legal for Catalans to exercise the same rights as Scots, thereby avoiding uncertainty and ensuring adequate respect for the principle of self-determination?

According to Pedro Sánchez, the acting Spanish President, Catalonia will “never” be independent and there will “never” be a referendum. According to Miquel Iceta, the leader of the Catalan branch of the anti-independence Spanish Socialist Party, there should not be a recognized referendum because “Catalans don’t want one”. The position of the Spanish government is that there is not sufficient consensus to even consider a referendum in Catalonia.

Here’s the thing, though. There already does exist a consensus among Catalans. It existed in 2017, when they were beaten and jailed for attempting to vote. It continued to exist in 2018, as Catalan political leaders waited in pre-trial prison. And exists right now, in 2019, per the most recent polling data. Catalans – including many who do not want independence – want what Scotland has: the ability to decide their form of government for themselves. They want a referendum.

The data

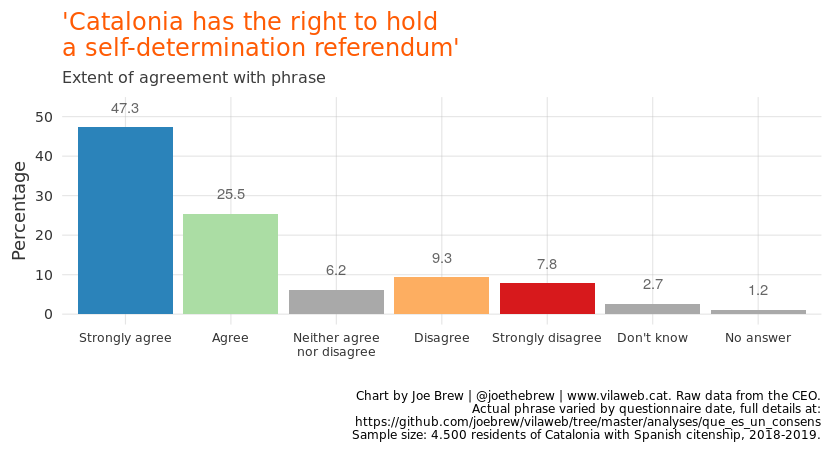

The Baròmetre d’Opinió Política of the Centre d’Estudis d’Opinió occasionally asks Catalans whether they feel that Catalonia has a right to hold an independence referendum. Since the 2017 referendum, the question has been asked 3 times, in 3 different ways:

- June 2018: Extent of agreement with the phrase “Catalonia does not have a right to celebrate a self-determination referendum”.

- March 2019: Extent of agreement with the phrase “Catalans have a right to decide their future as a country by voting in a referendum”.

- June 2019: Extent of agreement with the phrase “Catalonia has the right to celebrate a self-determination referendum”

The three variations of the question are essentially asking the same exact thing (albeit in the negative form in the first iteration, requiring transformation of the data). Let’s explore the response to this question, and – for the sake of avoiding potentially misleading variations associated with small sample size

- let’s aggregate the values for 2018 and 2019.

The below shows the opinions of a representative sample of 4.500 Catalans on the question of self-determination. Nearly three-quarters believe that Catalonia has the right to hold a self-determination referendum. Only 17,1% feel that it does not.

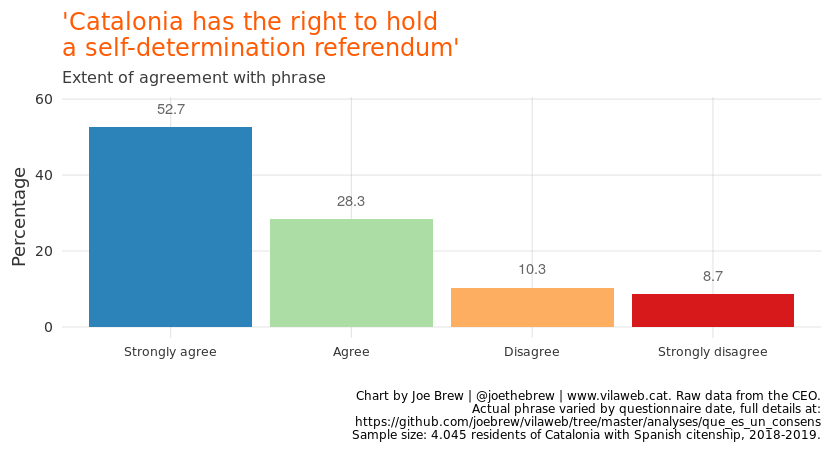

If we remove those who didn’t give an answer one way or the other, we get the following:

In other words, 19% of Catalans oppose Catalan self-determination, and 81% are in favor.

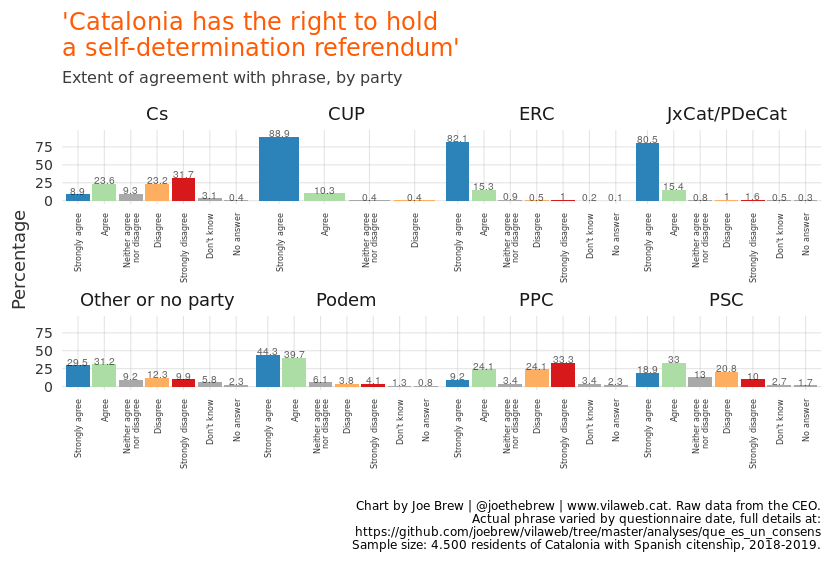

What’s striking about this figure is that it completely invalidates Spanish President Pedro Sánchez’s excuse for not taking any political measures to resolve the Catalan conflict. Sánchez stated last year that he would consider any political propsoal if it were to obtain the support of “75 to 80% of Catalan society”. Self-determination has the support of 81% of Catalans. Why, then, has Sánchez not budged from his position of “never” holding a referendum? But what’s even more striking is how much support there is for a self-determination referendum, even among voters of Pedro Sánchez’s party. More than half of Catalan socialists believe Catalonia has a right to a self-determination referendum, and fewer than 31% believe that Catalonia does not.

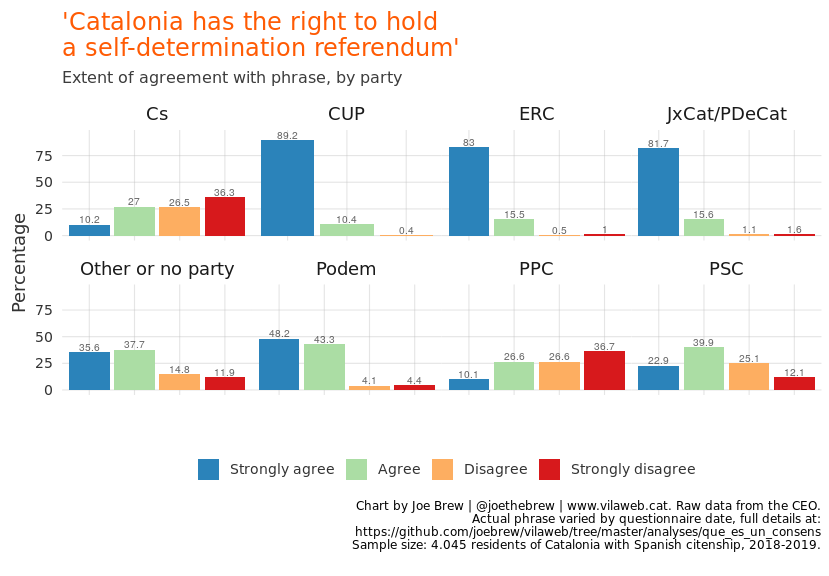

Again, if we remove those who did not answer the question one way or another, the breakdown by party is even more telling.

More than 60% of Catalan socialists – a party whose Catalan leader claims that Catalans don’t want a referendum – themselves say that Catalans have a right to a self-determination referendum.

Conclusion

Scottish Prime Minister Nicola Sturgeon has announced that her government will pursue an independence referendum in the next two years. Though some Tories have stated that they will actively oppose it, many UK politicians – including those in anti-independence and anti-referendum parties – have stated that they will accept it. As John McDonnell, the shadow chancellor of the Labour party, stated last week: “We would let the Scottish people decide. That’s democracy”. John Corbyn, the leader of the Labour party, apparently shares that view.

Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s President, asked for 80%. And he got it. 81% of Catalans believe that Catalonia has a right to a self-determination referendum. The fact that Pedro Sánchez is not undertaking the legal measures to ensure that a referendum can be carried out suggest that he is simply not aware that this consensus exists.

Or, and sadly perhaps more likely, Pedro Sánchez is aware that a broad consensus exists in Catalonia in favor of Catalan self-determination. But he’s likely also aware of the broad consensus in Spain against allowing Catalans to decide for themselves. And denying Catalan self-determination wins votes in the rest of Spain.

But Sánchez needs to maintain the myth that Catalans are a divided society without a consensus to solve their political problems. To safeguard his votes in the rest of Spain, as well as his credibility in the rest of Europe, he needs people to believe that Catalans don’t even know what they want. This is the myth that allows the Spanish State to postpone implementing the obvious solution to the Catalan political crisis, the solution desired by a large majority of Catalans, the solution carried out in Scotland, and the solution implemented in all other recent cases of sizeable independence groups nearing the 50% threshold in democratic societies: a referendum.

Technical note

All code and data for this article are publicly available at: https://github.com/joebrew/vilaweb/tree/master/analyses/que_es_un_consens.