23.08.2019 - 14:21

|

Actualització: 23.08.2019 - 16:21

If you are a reader of Spanish print newspapers, you might think that Barcelona erupted into a civil war this month. The headlines refer, day after day, to violent crime, homicide, robberies, riot police, and the general issue of insecurity.

Politicians, particularly those from the political right, have hopped on board as well, calling the situation in Barcelona an “emergency” and denouncing the leftist mayor of Barcelona, Ada Colau.

So, are they right? Is the increase in cases of crime in Barcelona a reflection of reality, or of a “relat” (narrative)? Let’s explore the data.

The reality

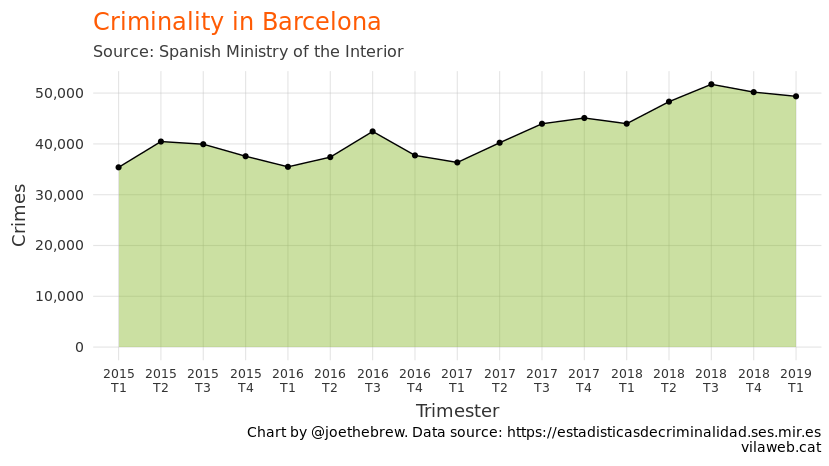

Reliable data on crime in Barcelona are available from two sources: the Spanish Ministry of the Interior and the Catalan police (Mossos d’Esquadra). The Ministry data are likely the most comprehensive (including multiple police sources), but are only up to date through the first trimester of 2019 (and therefore largely irrelevant to the conversation about the current supposed crisis in security in Barcelona). The below shows the number of crimes in Barcelona per trimester, per the Ministry of the Interior:

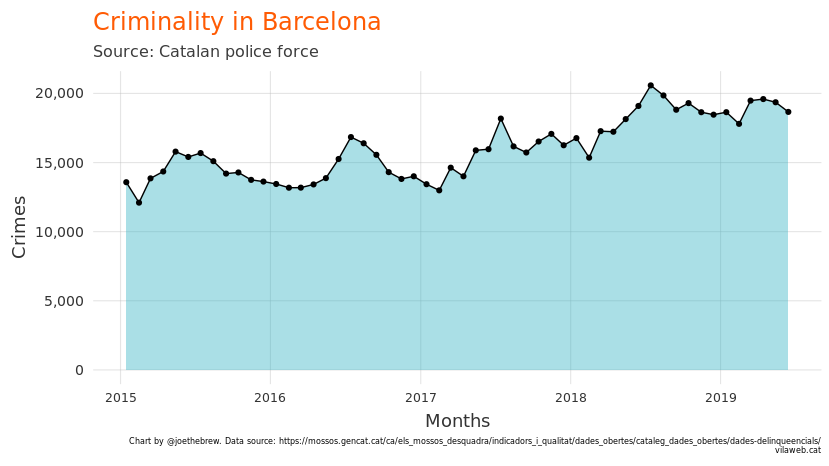

The data from the Mossos are more detailed (by month rather than trimester) and slightly more up to date (going through the end of June). The below shows crimes known to the Mossos over the last few years.

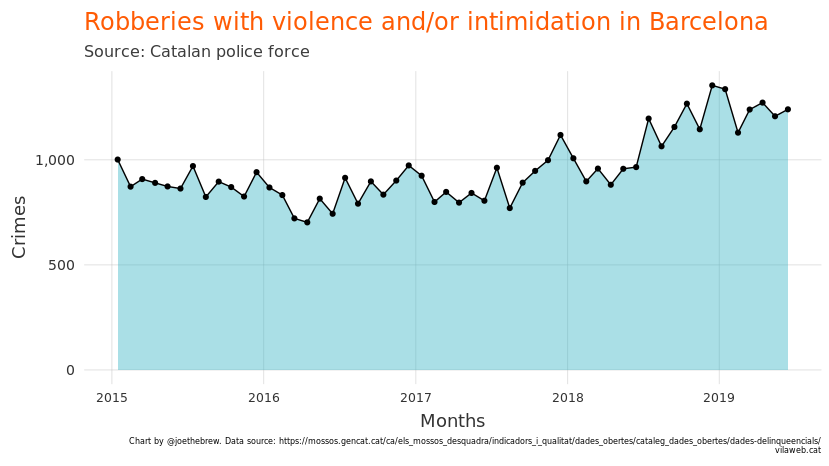

As can be seen above, there is certainly a gradual increase over time, but nothing extraordinary in the last few months. Let’s look more specifically just at violent robbery (the crime that gets the most attention in the media):

Again, there are notable increases over the last few years, but not especially in the last few months.

The relat (the narrative)

The data on criminality is pretty straightforward: crime is going up in Barcelona, but there has been no particular change over the last few months. And even with the increases this year, Barcelona remains safter than most other European cities.

But the narrative, in both the news media and social media, is not in close contact with reality. Whereas increases in crime in Barcelona have been gradual, talking about crime in Barcelona has skyrocketed over recent weeks.

For this analysis, we gathered 728053 tweets from 35 Catalan and Spanish newspapers. The full list can be seen at the end of this article. We identified all tweets which contained both the word “Barcelona” and a word referring to violence and/or crime (“violència”, “inseguretat”, “delictes”, “crim”) in both Spanish and Catalan.

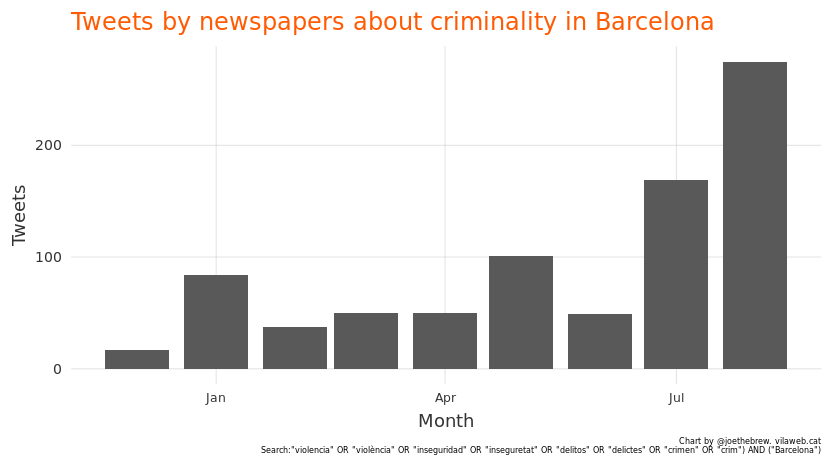

The below chart shows the combined number of monthly tweets from these 35 newspapers mentioning the crime situation in Barcelona:

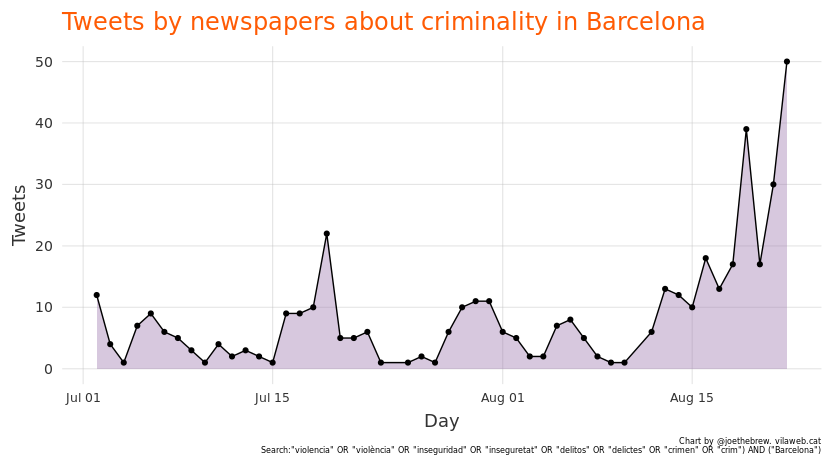

If we look by day over just the last few weeks, the rapid increase is even more striking.

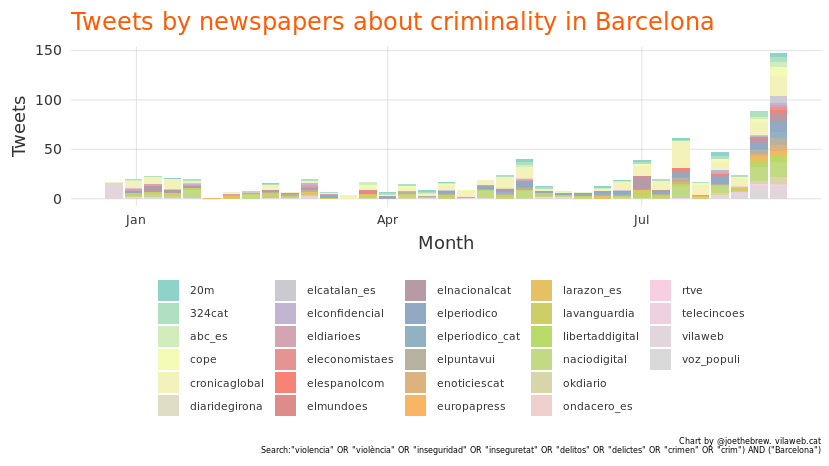

Let’s break it down by which newspapers, by week.

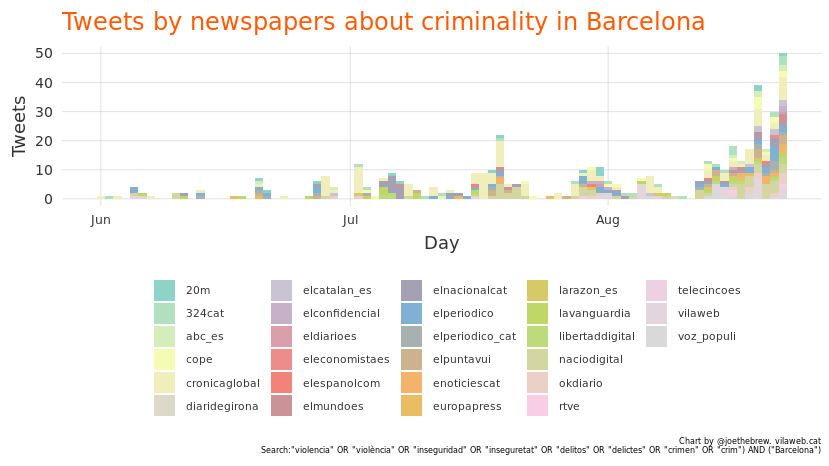

Finally, we can examine which newspapers by day:

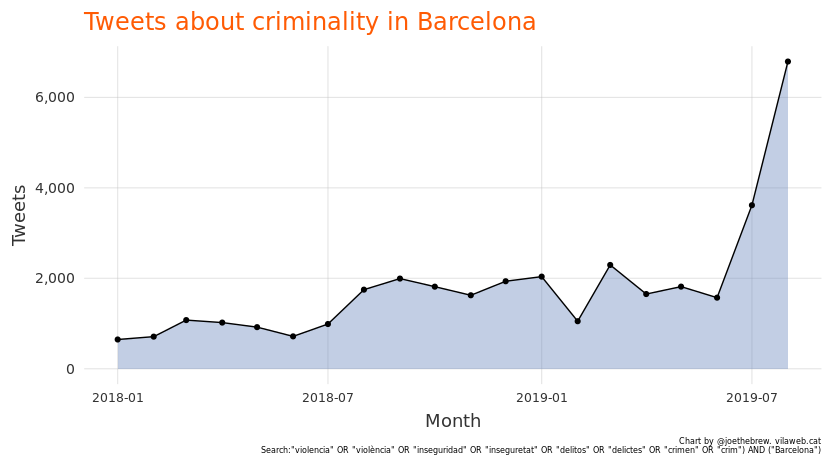

The increased newspaper coverage has had an effect on the general population. The below shows unique monthly tweets mentioning criminality or violence (using the same search query as above) and Barcelona in Twitter in general, since the beginning of 2018.

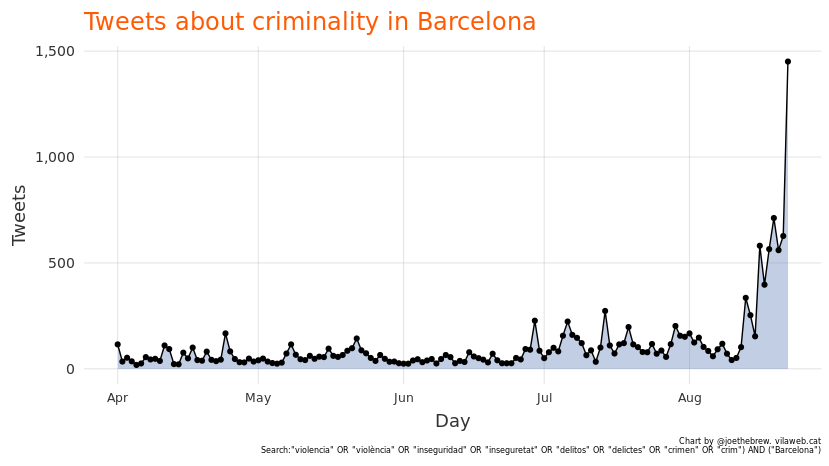

Let’s look at the same data, but at the daily level and only for the last few months. The below shows the number of daily unique tweets criminality or violence and Barcelona.

Comparing reality and narrative (relat)

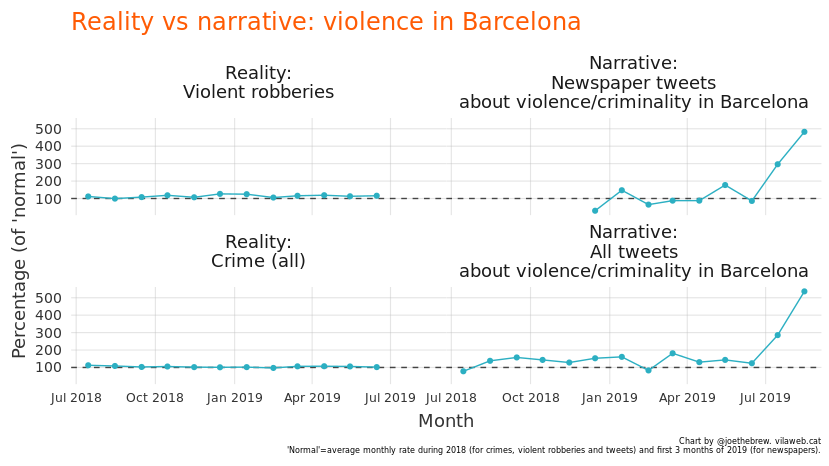

Let’s examine a comparison between reality and relat (narrative). The below chart shows “reality” on the left (known number of monthly crimes and violent robberies) and “relat” (narrative) on the right (tweets from both newspapers and the population as a whole mentioning violence and criminality in Barcelona). The numbers have been standardized to percentage of “normal”, ie 200% means that there is twice the normal rate, and 50% means there is half the normal rate.

Both reality and relat (narrative) show an increase in criminality and violence in Barcelona, but the proportionality is totally lacking. Whereas violent robberies were up 10-12% in the most recent months for which data is available realtive to “normal” (2018), tweets about violence and criminality in Barcelona increased by 500%.

Interpretation and Conclusion

Two things stand out in this analysis:

- Disproportionality of coverage: The disproportionality between the relatively moderate increases in criminality in Barcelona and the extreme increases in newspaper coverage about criminality in Barcelona.

- Timing of coverage: The arbitrariness of the timing of the newspaper coverage about criminality.

In other words, over the last month, reality and relat (narrative) diverged. With no new data available on crime since June, and with no data suggesting a particular uptick in the rate of crime in the last few weeks, newspapers – and people – began talking incessantly about crime in Barcelona. The rate hit fever pitch over the last week, with dozens of newspapers covering multiple stories on the security “crisis” in the Catalan capital.

Why did the increase take place now? And why is the (major) increase in coverage about violence and criminality in Barcelona so disproportionate to the actual (relatively minor) increase in violence and criminality?

It’s helpful to consider the importance of the mental “frame” of both journalists and their readers in trying to understand how a story catches fire, and what motivates editorial decisions. The case of the virality of the Barcelona-crime news angle could be an example of a “feedback loop” or “echo chamber”. It works like this: a violent event occurs (a stabbing, for example), journalists write about it, not much else is going on in the news these days, so the story about the violent event gets the most clicks, which motivates journalists to write more about violent crime in Barcelona, which feeds a sense of fear in the population, which motivates more people to click on and retweet stories about violent crime, which motivates journalists to write more about it, etc. As the echo chamber grows in volume, journalists from other news organizations feel obliged to also cover the story (since “everyone is talking about it”), and politicians must also comment on it. Then, more stories are written about what politicians said about it. And there are even stories about stories about it.

In the feedback loop, we are all at fault for the disconnect between reality and relat. In fact, we actively create that disproprtionality by choosing what to discuss, what to write about, what to like or retweet, and what to ignore. In this sense, journalism is demand-driven: we demand sensationality (as demonstrated by what we click on), and journalism provides. Classic economics: supply and demand. I myself am contributing to the feedback loop by choosing to write about criminality in Barcelona for this article.

But to say that all are to blame does not mean that all are to blame equally. Journalists have an ethical responsibility to maintain some allegiance to reality, even if this means passing on the opportunity to publish a “clickworthy” headline. When the institution of journalism does nothing to push back against a narrative which is increasingly decoupled from reality – and in some cases even contributes to the narrative – it fails to fulfill its responsibility to society.

Publishing headline stories on violent crime in Barcelona, day after day, at an unprecented rate, at an arbitrary moment in terms of the actual rate of crime, might be good for business – but it does not reflect well on the professionality of journalism. Sure, journalism should be demand-driven – journalists should write stories about the things people want to read about. But it should also be reality-driven. And in the case of Barcelona’s apparent crime “crisis”, reality plays only a minor role.

List of newspapers analyzed

20m

324cat

abc_es

cadanaser_espa

ccmaa_cat

cope

cronicaglobal

diariaara

diaridegirona

elcatalan_es

elconfidencial

eldiarioes

eleconomistaes

elespanolcom

elmundoes

elnacionalcat

elpais

elpais_espana

elperiodico

elperiodico_cat

elpuntavui

enoticiescat

europapress

larazon_es

lavanguardia

laverdad_es

libertaddigital

naciodigital

okdiario

ondacero_es

publico

rtve

telecincoes

vilaweb

voz_populi