20.09.2019 - 11:59

|

Actualització: 20.09.2019 - 13:59

There is a crisis in Catalonia – that much is clear. But knowing what kind of crisis Catalonia is going through depends on who you ask. To many Catalans, it’s a political crisis between Catalonia and Spain, in which the pro-referendum majority in Catalonia has been blocked by the anti-referendum majority in Spain from carrying out its political project. To Spanish PM Pedro Sánchez, it’s a crisis of ‘convivencia’ (coexistence) between Catalans thesmelves, in which the half in favor of independence has sought to ‘impose’ its political project on the half opposed. And the Spanish justice system is treating it as crisis of violent crime, having imprisoned most of the former members of the Catalan government on charges of ‘rebellion’.

But what is the true nature of the crisis in Catalonia? Beyond the rhetoric of politicians, why is Catalonia going through major political turmoil whereas other areas – Andalucia, Flanders, Texas, Brittany – are not.

Current events in Catalonia reflect a crisis of legitimacy more than anything else. Both the Head of State who rules over Catalonia symbolically, and the Spanish Constitution which rules over Catalonia juridically, receive the support of fewer than half of Catalans. The ‘Statute of Autonomy’, the legal contract which governs the relationship between Catalonia and Spain, is not the same version as the one approved by Catalans via a popular vote in 2006 (that version had parts stricken from it by Spanish Courts). And even the transition from fascism to democracy in the late 1970s, a point of pride for most Spaniards, is seen by most Catalans as having been poorly carried out.

Democratic legitimacy stems not just from the existence of a set of laws, but also from a general acceptance of the system by which the laws are generated. For example, in the USA, though nearly half of voters are unsatisfied with the outcome of any specific presidential election, significant majorities in every one of the 50 States approve of the system by which the voting took place. The reason democracies can be considered more ‘legitimate’ than autocracies is not that the former are governed by rules and the latter aren’t (in fact, both have rules, and autocracies can very much fit the definition of ‘estado de derecho’ and ‘rule of law’); rather, it’s that the processes and rules which govern society are perceived and accepted by the population as appropriate and fair (aka ‘legitimate’).

The political framework governing Catalonia does not receive enough popular support among Catalans to ensure political stability. This much is obvious from simply observing the last few years of Catalan and Spanish politics (a contested referendum in the first case, 4 national elections in less than 4 years in the latter). In other words, the Catalan crisis is a crisis of ‘legitimacy’. This is not simply an opinion: it’s a fact backed up by data on the subject.

Let’s explore those data. Specifically, let’s examine survey data regarding how Catalans feel about Spain’s transition to democracy, the Spanish Constitution, the possibility of favorable negotiations with Spain, and the principle of self-determination. Here we go.

The transition to democracy

Following the death of dictator Francisco Franco in 1975, Spain began it’s multi-year transition to democracy (known simply as ‘La Transición’ in Spanish). This involved opening up to free elections, replacing fascist institutions with nominally democratic ones, allowing for political parties, etc. The “Transition” was applauded by much of Europe and the United States, but was not endorsed by all. Controversially, it kept in place the Franco-appointed Bourbon monarchy, and involved a controversial ‘Amnesty’ law which meant that crimes committed by the Francoist regime would go uninvestigated and unpunished.

In 2018, the CIS (the Spanish national Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas) asked 3.000 Spaniards whether they thought the transition was a ‘source of pride’. For most (more than 80% in non-Catalonia Spain), it is. But in Catalonia, fewer than half consider the Transition to be a source of pride.

Endorsement of the Spanish Constitution

It’s not entirely clear why the rates of ‘pride’ in the transition differ so drastically between Catalans and Spaniards. But it likely has at least something to do with the most tangible product of that transition: the Constitution.

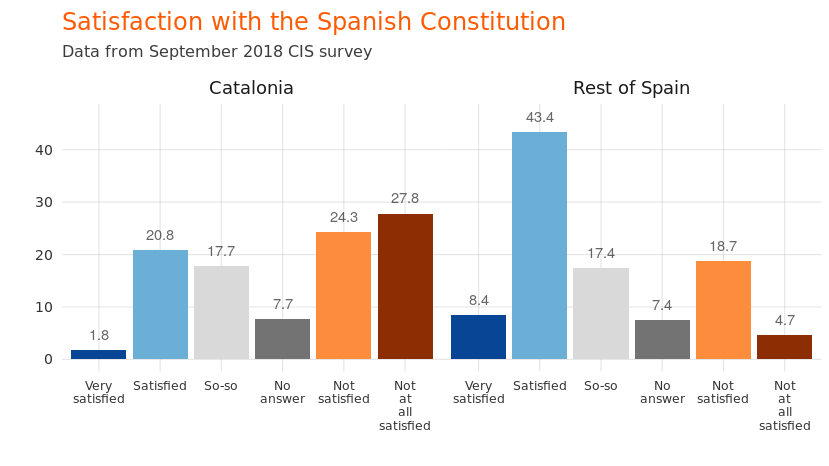

The 1978 Constitution was approved in referendum by a vast majority of Spaniards (including Catalans). At the time of the referendum, the choice was rather stark (‘Yes’ meaning a transition to democracy, ‘No’ meaning political uncertainty with a non-negligible chance of continued fascist rule). But 40 years later, the percentage of Catalans who are satisfied (22.6%) is less than half of the satisfaction rate among Spaniards from the rest of the State (51.8%). Most Catalans (52.1%) are dissatisfied with the Spanish Constitution.

When it comes to the Constitution, Catalonia is not the only part of the Spanish State with higher levels of dissatisfaction than satisfaction. The Basque Country and Navarra are similarly dissatisfied with the State’s Magna Carta (note, these regions – like Catalonia – are historical nations with their own language).

In fact, when asked if they would vote for the Spanish Constitution if there were a referendum on it now, a large majority of Catalans say that they would not. Only 17.4% say that they would vote in favor of the current Constitution.

Nostalgia for Franco

It’s not only noteworthy that so few Catalans would vote in favor of the current Constitution. It’s also interesting to look at which Catalans are for and against the Constitution. The below chart shows how Catalans would vote if there were a referendum on the 1978 Constitution as a function of their views on Franco.

Catalans who think that the Franco period was negative for Catalonia (the 3 left-most bars) would vote overwhelmingly against the 1978 Constitution (67% vs 12%). Those with mixed views on Franco (the three middle bars, who say the Franco period had both good and bad aspects) would also vote against the Constitution (38 vs 30%), albeit not by so much. The only group where there is a clear pro-Constitution majority is among those Catalans who say that the Franco period was ‘positive’ for Catalonia – in this group, ‘Yes’ to the Constitution would win by a margin of almost two to one.

The Left-Right divide and the Constitution

Part of the reason pro-Franco attitudes are so entwined with support for the Spanish Constitution in Catalonia is because the Spanish Constitution is perceived as partisan by Catalans. In other words, support for the Constitution is far greater among people who identify as being on the ‘right’ or ‘far right’ of the political spectrum than among those who identify as being on the left:

Whereas only 10-12% of leftist Catalans would vote in favor of the 1978 Constitution if there were a referendum held on it today, support doubles in the political center, triples in the political right, and quadruples in the political far-right. In other words, the more to the right, the more support for the Constitution.

The left-right association with support for the Constitution is not unique to Catalonia. In the rest of the Spanish State, satisfication with the Constitution is far greater among those who self-classify on the political ‘right’ than the ‘left’. The below chart shows satisfaction with the Spanish Constitution as a function of political ideology, among people from Spain (not including Catalonia):

Support for the Constitution in Spain is generally higher than in Catalonia, but the satisfaction pattern follows the same curve: Dissatisfaction with the Constitution is high among those on the left (34.4%), and low among those on the right (14.9%).

The Left-Right divide and the King

Like with the Constitution, support for the Spanish King is also closely associated with political ideology among Catalans. The below chart shows Catalans approval rating for King Felipe de Bourbon (and his predecessor, Juan Carlos) over the last 5 years.

Greater than half of Catalans give the Monarchy a score 0 out of 10. Only around 1 in 10 give a passing grade (greater than 5).

By ideology, it’s clear where most of the Monarchy’s support comes from. The average approval rating for the Monarchy (‘grau de confiança’) among the far left is approximately 1 out of 10. But approval is 4 times higher on the right, and even higher on the far-right:

Loss of faith in negotiation

We have established that neither the Spanish Constitution, nor the Insitution it created (the Spanish Monarchy) receive significant support in Catalonia. And much of the (relatively low) support for the Monarchy and Constitution stem from the political right and those who see the Franco period as ‘positive’. So, if the Monarchy and Constitution are both unpopular and politicized, why don’t Catalans work out a deal with Spaniards to change, reform, depoliticize, or remove them? Why, in 2017, did Catalans ‘unilaterally’ (ie, without permission from Madrid) carry out an independence referendum?

The answer is fairly clear: they’ve given up hope that a mutually agreed upon deal can be worked out.

A large majority of Catalans want a self-determination referendum. Only 19% of Catalans say that Catalonia does not have a right to one:

But on the question of a self-determination referendum, the position of the current Spanish President Pedro Sánchez is identical to that of the previous President, Mariano Rajoy: ‘Never’. The refusal to even discuss self-determination has lead most Catalans to believe that it is unlikely Spain will ever offer a satisfactory agreement to Catalonia. The below chart shows how the percentage of Catalans who believe that a satisfactory offer from the Spanish Government is not probable has grown from two thirds to three fourths over the last few years:

As of the most recent time this question was asked (2017), only 2 in 10 Catalans believed it was probable that Spain would offer an acceptable political solution to Catalonia. If you were wondering why Catalans acted ‘unilaterally’, that’s your answer.

Why are Catalans so sceptical that Spain is capable of making an offer which will be politically acceptable to them? Two reasons. First, the Spanish Government has made very clear that self-determination is off the table, and will not even discuss the issue. Second, outside of Catalonia, any Spanish politician who proposes the possibility of independence (or even more autonomy) is committing political suicide. Why? Because the percentage of Spaniards who are satisfied with the status quo, or want less autonomy for regions, is a huge majority. The below chart shows these differences in preferences for territorial organization:

Conclusion

The political deadlock in Catalonia is not caused by ‘criminal’ politicians. Nor is the cause of the crisis the economy, a lack of ‘convivencia’ (coexistence), nationalism, populism, a ‘coup d’etat’, a ‘rebellion’, or any of the other semi-absurd, simplistic, explanations. The data make very clear what the actual three underlying issues are:

- A majority of Catalans want to exercise their right to self-determination

- A majority of Spaniards do not want permit them to exercise that right

- The institutions and processes by which this conflict could be resolved ‘internally’ are not perceived as sufficiently legitimate by one side to be effective for both sides

It’s this third point which leads me to describe the Catalonia-Spain political crisis as one of legitimacy. One side (Catalonia) wants something (self-determination) that the other (Spain) won’t agree to. And the current framework for deciding how to move forward (the Constitution) is not accepted by a large majority of one side. And the supposed ‘aribtrator’ for these kinds of conflicts, the Spanish King, is also not accepted by a large majority of one side.

If Catalans and Spaniards disagree about territorial organization, the legitimacy of the Constitution, and the legitimacy of the Monarchy, how can the conflict be resolved? The current approach of the Spanish State (insisting that Catalan politicians disobey their voters and instead obey Spanish law) is obviously unsustainable and is already generating significant political instability for Spain as a whole. For both the good of Spain and Catalonia, other approaches have to be explored.

Ultimately, what the Spain-Catalonia crisis needs is an injection of legitimacy, a process which is perceived as fair and satisfactory to both sides. This injection of legitimacy should come in the form of an external, transparent, binding process, with a mutually accepted arbitrator, one whose legitimacy is accepted by both sides. The European Union meets this definition and should actively pursue a role as mediator. If the EU continues to ignore the conflict, or downplay it as an ‘internal issue’, the likelihood of further ‘unilateralism’ (both in the form of Spain taking direct rule over Catalonia, or Catalonia again voting without Spain’s permission) is increasingly likely.